Alan Boyle, Science Editor

NBC News

Monty Sloan via UCLA

Modern-day wolves like these are closely related to dogs, but how

closely? Genetic sequencing showed no clear lineage that led from wolves

to dogs.

The latest genetic study to trace the origins of dogs confirms the view that they were

domesticated by hunter-gatherers at least 9,000 years ago — but the results raise almost as many questions as they answer.

Exactly what kind of wolf gave rise to "man's best friend"? Did domestication take advantage of a

rare genetic quirk, or did early humans merely take advantages of wolfish traits?

The study published on Thursday in the journal

PLOS Genetics

doesn't resolve those questions. But one of its senior authors,

University of Chicago geneticist John Novembre, says researchers are

working on ways to get the answers.

"Ancient DNA studies are going to be very exciting for this field in the near future," he told NBC News in an email.

Novembre

said Thursday's study complements earlier work that analyzed

mitochondrial DNA from modern-day wolves as well as ancient wolf

remains. It suggests that dogs descended from a wolf strain that has

since gone extinct. The genetic tale is complicated, however, due to

interbreeding between dogs and wolves in recent times.

Unexpected results

The

PLOS Genetics study relies on detailed analyses of the genomes for two

dog breeds, a dingo from Australia and a Basenji whose lineage goes back

to Africa. The genomes for three wolves living in different parts of

the world — Croatia, Israel and China — were also analyzed. To round out

the picture, the researchers sequenced the genome of a golden jackal

and included the previously published genome of a boxer from Europe.

The

wolves were selected to represent the three regions of the world that

have been identified as the potential points of origin for domesticated

dogs: Europe, the Middle East and Asia. "These are the highest-quality

wolf genome sequences published to date, and among the very first,"

Novembre said. "Without high-quality wolf genomes, it's difficult to

learn about the origins of dogs."

He and his colleagues expected

to find that the dog breeds had closer genetic connections to one of the

wolves over the others. That would have provided a new clue in the

detective story, but that's not what happened. Instead, the results

suggested that the Basenji and the dingo both descended from an older,

wolflike ancestor.

"Perhaps the closest lineage of wolves to dogs

went extinct and is not represented well by modern wolves," Novembre

said. "The ancient mitochondrial DNA paper suggests that the ancient

lineage of wolves may have existed in Europe."

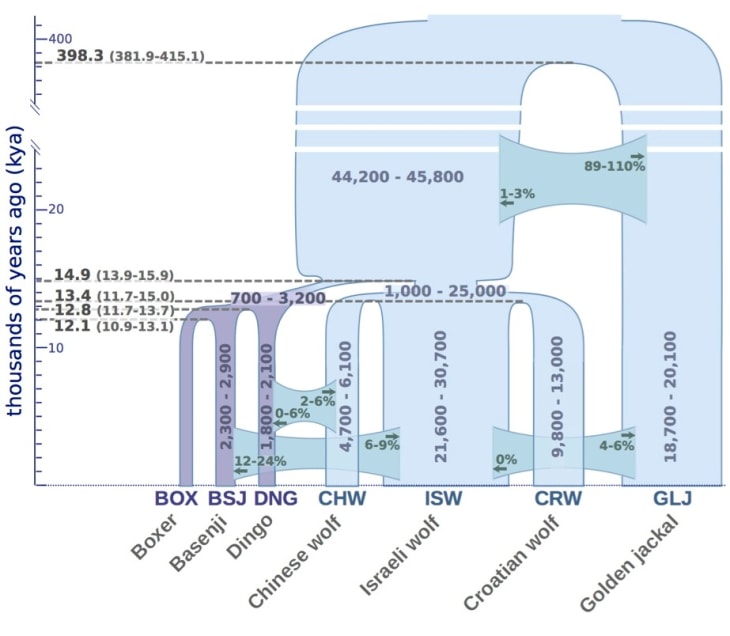

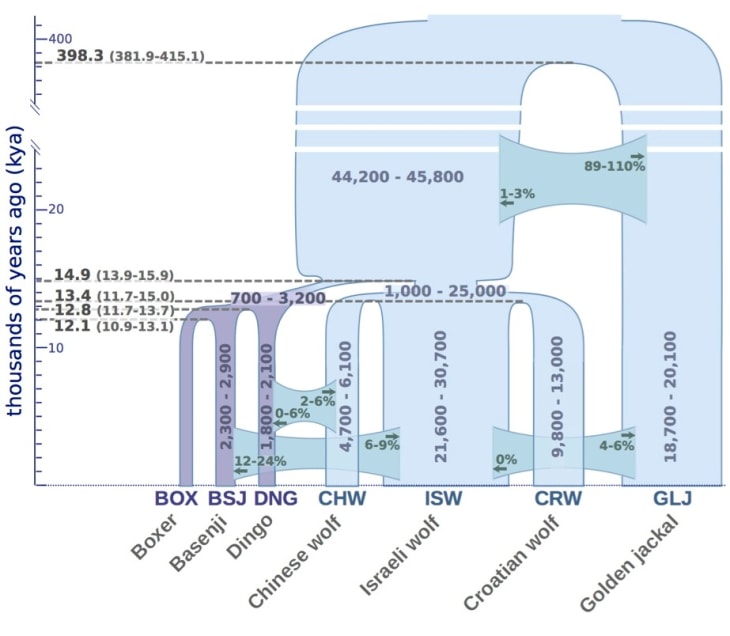

Freedman et al. / PLOS Genetics

This chart sketches out how genetic relationships evolved over time,

based on the genomes of three dogs, three wolves and a jackal. The

estimated time frames rely on assumptions about mutation rates.

Hunting vs. farming

The

earlier research estimated that domestication occurred sometime between

18,000 and 32,000 years ago. This week's paper cites a similarly wide

range of dates, from 9,000 to 34,000 years. Both time frames predate the

rise of agriculture, which occurred several thousand years ago. Those

findings favor the view that dogs started out as hunting companions

rather than village scavengers.

Novembre and his colleagues also followed up on earlier findings that

dogs adapted to digest starch,

perhaps due to their proximity to human agricultural settlements. They

determined that most dogs do indeed have high numbers of the amylase

genes that promote starch digestion. However, that's not the case for

dogs that lack a close connection to agrarian societies, such as

Siberian huskies and dingoes.

The researchers found evidence for

amylase genes in wolves, too. Taken together, the findings lend further

support to the hunting-dog scenario: Dogs probably started out mostly as

meat-eaters, but gradually adapted to a starchy diet when they had to.

The

genetic record suggests that dogs went through a narrow population

"bottleneck" after they diverged from wolves. Wolves went through a

similar bottleneck, and that may have been when the breed of wolf that

gave rise to dogs died out. Why did the bottleneck occur? That's another

question yet to be answered.

"Presumably, changes in habitat and

prey availability as humans expanded and altered landscape is part of

the story," Novembre said.

More about the debate over dog origins:

In addition to Novembre, the authors of "Genome Sequencing Highlights the Dynamic Early History of Dogs" include Adam H. Freedman, Ilan Gronau, Rena M. Schweizer, Diego Ortega-Del Vecchyo, Eunjung Han, Pedro M. Silva, Marco

Galaverni, Zhenxin Fan, Peter Marx, Belen Lorente-Galdos, Holly Beale,

Oscar Ramirez, Farhad Hormozdiari, Can Alkan, Carles Vilà, Kevin Squire,

Eli Geffen, Josip Kusak, Adam R. Boyko, Heidi G. Parker, Clarence Lee,

Vasisht Tadigotla, Adam Siepel, Carlos D. Bustamante, Timothy T.

Harkins, Stanley F. Nelson, Elaine A. Ostrander, Tomas Marques-Bonet and

Robert Wayne.

Alan Boyle is NBCNews.com's science editor. Connect with the Cosmic Log community by "liking" the NBC News Science Facebook page, following @b0yle on Twitter and adding +Alan Boyle to your Google+ circles. You can also check out "The Case for Pluto," my book about the controversial dwarf planet and the search for new worlds.